The Rise of Humanism and Its Impact on Renaissance Thought

The Renaissance, which spanned from the 14th to the 17th century, was marked by an intellectual and cultural rebirth that profoundly reshaped Europe. Central to this transformation was the rise of Humanism, a movement that placed human beings at the center of the intellectual world. Humanism emphasized the study of classical antiquity—Greek and Roman philosophy, literature, and art—and focused on human potential, individualism, and secular knowledge. This shift away from the strictly religious worldview of the Middle Ages had a lasting impact on Renaissance thought, education, and art.

Humanism’s Classical Roots

The seeds of Humanism were sown in the late Middle Ages as scholars in Italy began rediscovering ancient texts by classical authors like Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Virgil. For centuries, much of this knowledge had been lost or ignored in favor of religious and theological texts. However, by the 14th century, scholars such as Petrarch—often considered the “Father of Humanism”—sought to revive these ancient sources and promote their study as a path to intellectual and moral improvement.

Humanists believed that studying the classics would lead to a better understanding of human nature and the world. They rejected the scholasticism of the medieval period, which focused on religious dogma and rigidly structured debates. Instead, Humanism celebrated individual inquiry, critical thinking, and the exploration of secular subjects like history, ethics, and literature.

Key Figures of Humanism

Petrarch (1304–1374) was one of the earliest and most influential Humanists. He believed in the potential of the individual to achieve greatness through knowledge and self-reflection. His famous letters to ancient figures like Cicero symbolized his desire to communicate with the great thinkers of the past and bring their wisdom into the modern world. Petrarch’s belief that humans could shape their own destinies through education and reason became a hallmark of Humanist philosophy.

Following in Petrarch’s footsteps was Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), whose work The Decameron is not only a cornerstone of Italian literature but also an important document of Humanist values. The Decameron presents a series of stories told by a group of people fleeing the plague, highlighting themes of love, fortune, and human behavior. Boccaccio’s vivid portrayal of the complexities of human life, with both its virtues and vices, embodied the Humanist fascination with human experience.

Another key figure was Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457), a scholar and priest who exemplified the Humanist desire to apply critical thinking to all areas of knowledge, including religious texts. His famous work, On the Donation of Constantine, used philological analysis to prove that a document granting political power to the Pope was a forgery. Valla’s critical approach to historical sources reflected the growing Renaissance belief in questioning authority and relying on evidence.

Humanism’s Impact on Education and Society

One of the most significant impacts of Humanism was its influence on education. The rise of Humanism led to the establishment of new curricula in universities that prioritized the studia humanitatis, or the study of the humanities. This curriculum included grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy—subjects drawn from classical antiquity that were designed to cultivate a well-rounded, virtuous individual.

This focus on the humanities marked a significant shift from the medieval educational system, which had been dominated by theology and logic. Humanists believed that education should not only prepare individuals for religious vocations but also equip them for active participation in civic life. This idea, known as civic humanism, encouraged individuals to apply their knowledge to improve society. Thinkers like Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) promoted the idea of the “Renaissance man”—a person who is skilled in multiple fields and can contribute to the common good.

Humanism’s emphasis on individual potential also encouraged people to challenge long-held beliefs and authorities. The notion that humans could rely on reason and experience to understand the world laid the groundwork for the scientific inquiry and innovation that characterized the later Renaissance. Humanism played a key role in the Scientific Revolution, inspiring thinkers like Galileo and Copernicus to question established knowledge and seek new explanations for natural phenomena.

Humanism and the Arts

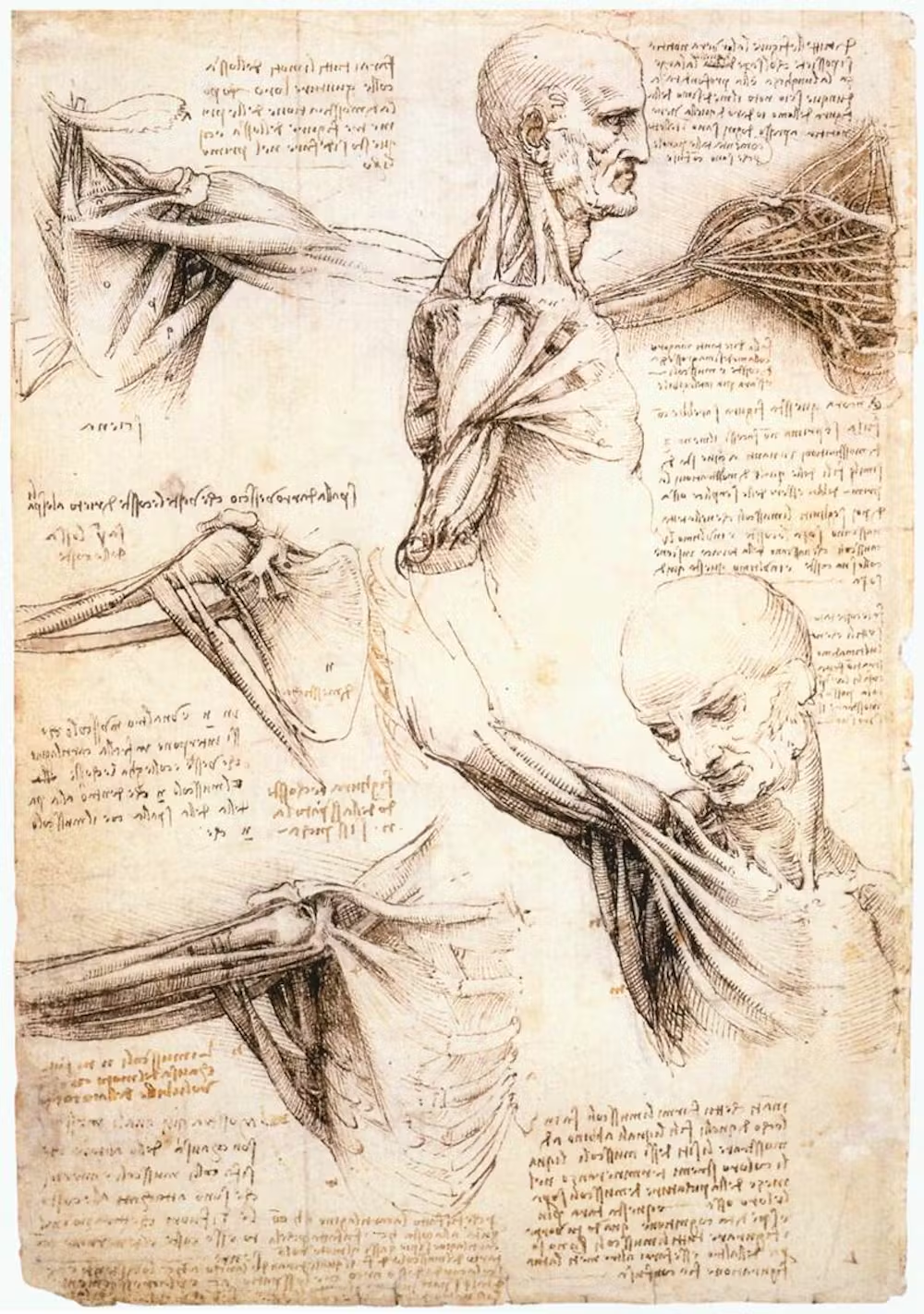

In the realm of art, Humanism had a profound influence on how artists approached their work. Whereas medieval art had focused almost exclusively on religious themes and followed strict conventions, Renaissance artists, inspired by Humanist ideals, sought to portray the human experience in all its richness and variety. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo studied human anatomy to create lifelike depictions of the human form, reflecting the Humanist belief in the beauty and potential of the individual.

Leon Battista Alberti, an architect and Humanist scholar, wrote treatises on painting and architecture that emphasized the importance of proportion, perspective, and harmony—principles drawn from classical antiquity. These ideas would shape the work of Renaissance artists and architects, who sought to combine beauty with balance, order, and realism.

Humanism also encouraged artists to explore secular themes. Mythology, history, and portraits became popular subjects alongside traditional religious works. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, for example, depicts the classical goddess of love in a celebration of both beauty and classical mythology, while Michelangelo’s David glorifies the human form and individual heroism.

Humanism’s Broader Impact

Beyond education and the arts, Humanism had a wide-ranging impact on European society. It fostered a spirit of intellectual inquiry and debate, which would shape the political and religious movements of the era, including the Protestant Reformation. Humanist scholars like Erasmus called for a return to simple Christian piety and criticized the corruption within the Catholic Church, helping to lay the intellectual groundwork for reform.

Humanism’s emphasis on secular knowledge and critical thinking also influenced political thought. Figures like Niccolò Machiavelli applied Humanist principles to politics, advocating for pragmatism and a focus on human behavior in his famous work The Prince. This approach marked a departure from the medieval view of politics, which had been closely tied to religious authority.

Conclusion

The rise of Humanism was a defining feature of the Renaissance, bringing a new focus on the potential, dignity, and beauty of the individual. Through the revival of classical learning, Humanism reshaped education, the arts, and intellectual life, setting the stage for the remarkable achievements of the Renaissance. Its influence can be seen in the works of artists, thinkers, and writers who sought to explore the richness of the human experience and challenge the boundaries of knowledge. In doing so, Humanism laid the foundation for modern thought, encouraging individuals to seek truth, question authority, and celebrate the power of human reason and creativity.